Mary Harron Sets the Record Straight on Patrick Bateman

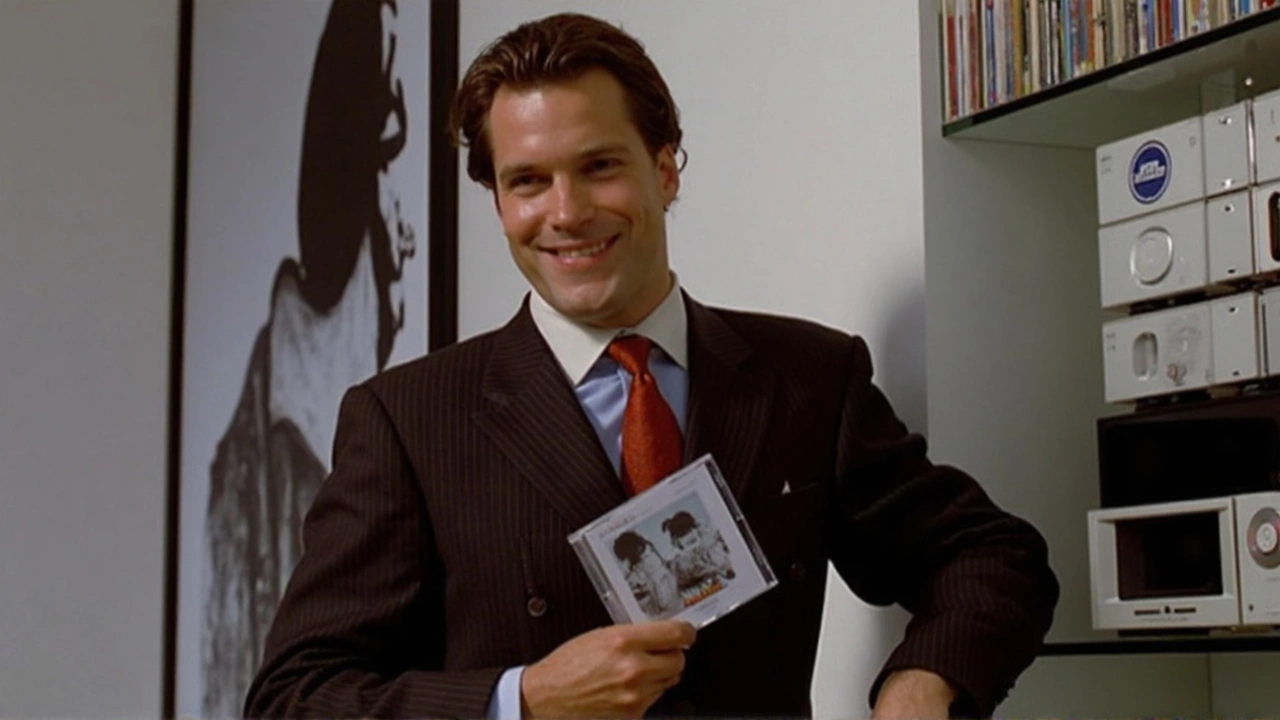

Plenty of people have walked away from American Psycho quoting Patrick Bateman, dressing up like him, and even calling him a hero. But Mary Harron, the director, says the movie’s point couldn’t be further from that idea. According to Harron, far too many fans look at Bateman as a smooth, successful guy—when in reality, he’s a walking punchline. The film was always supposed to be a knife in the side of 1980s Wall Street greed and the hollow performance of toxic masculinity.

Harron doesn’t mince words when she calls Bateman a “buffoon.” He’s a caricature, dripping in designer suits and vapid consumerism, acting out a version of alpha-male bravado that’s more pitiful than impressive. Despite all the glossy surfaces, Bateman is empty on the inside—he spends his days obsessing over business cards and pop songs, trying desperately to look like he fits a mold he doesn’t understand. The point, Harron says, is to laugh at him, not with him. His attempts to act tough or superior, or to borrow bravado from 1980s hip-hop culture, are supposed to look ridiculous, not desirable.

Satire Missed: When Audiences Idolize the Joke

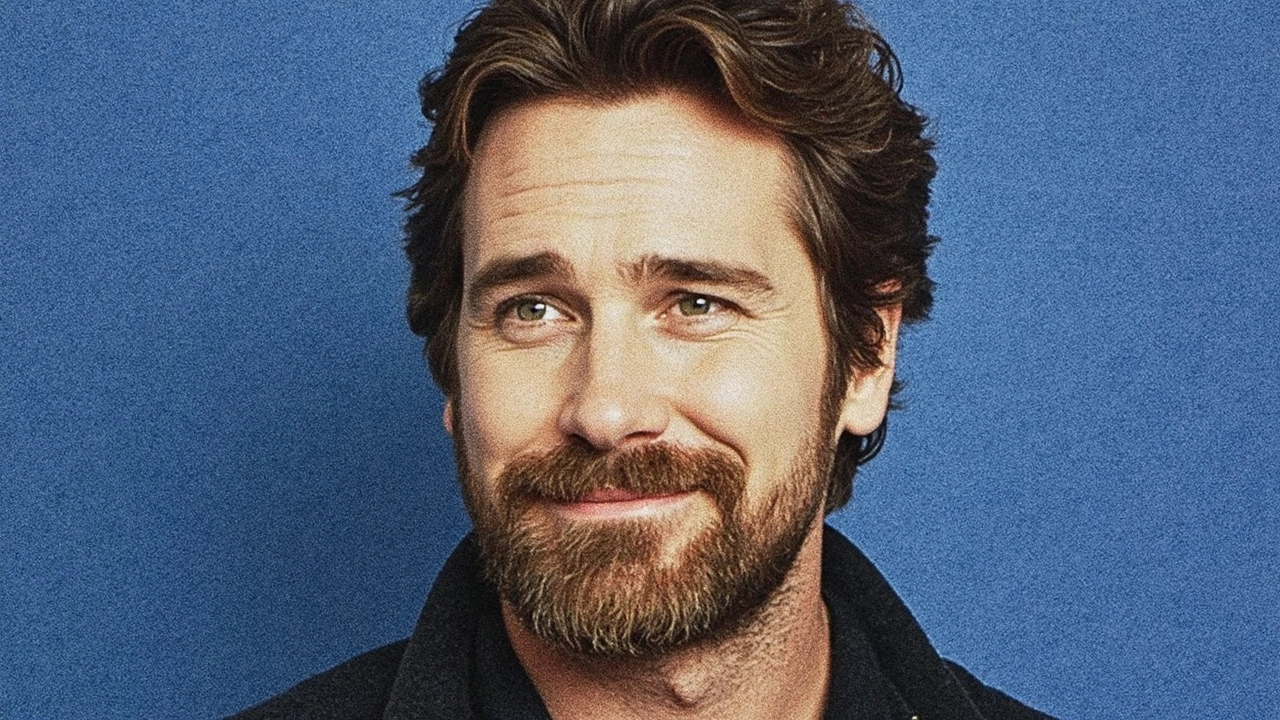

Here’s where things get weird. Harron and Christian Bale—who brought Bateman to life with chilling accuracy—have both run into real-life finance professionals and so-called Wall Street bros who claim Bateman as a kind of spirit animal. Harron is baffled, frustrated that anyone would miss that Bateman represents everything wrong with their culture: the vanity, the elitism, the relentless competition, and the emotional hollowness. Instead of recognizing the joke, some watch the film and walk away admiring the mask, not the message.

Bale has shared stories of traders grinning at him, delighted to meet “Patrick Bateman” in the flesh, eager to share how the character inspired them. Rather than seeing Bateman as a warped product of a broken society—a satire poking fun at the values of their world—they see him as aspirational. That’s not just missing the point; it turns the message inside out.

Harron stresses repeatedly that Bateman’s violence, narcissism, and faith in the power of brands aren’t objectives to aim for. They’re a warning about what happens when people value image over substance, status over humanity. The film’s sharp humor and absurd scenes were designed to expose, not excuse, the toxic blend of privilege and performative identity running rampant in certain circles. Bateman was always meant as a cautionary tale—a reflection in a warped funhouse mirror, showing us the ugliest side of ambition and class obsession.

- Bateman’s obsession with surface details mocks materialistic culture.

- His violence and coldness signal a total lack of empathy, not something to emulate.

- The film’s tone is satirical, ridiculing rather than revering.

By turning Bateman into a role model, fans are embracing the very flaws Harron set out to skewer. For her, the story isn’t about admiring Bateman’s lifestyle or attitude; it’s about understanding the emptiness of that world—and having a good laugh at how absurd it all is.